Please Keep On the Grass

Connecting to Nature During Challenging Times

I was walking through my neighborhood, just walking, when I heard it – a sharp, piercing sound. It was a whistle. Not the kind used to hail a cab or pass time but a commanding whistle, pointed and domineering. The kind of whistle used on dogs. Except it was for me.

The whistle came from a maintenance man patrolling a stretch of grass in front of an apartment complex. The grass is littered with leaves, nothing pristine, but he’d called me out. And sure, we could say that maybe this guy was just doing his job. Maybe he was following whatever orders his boss gave him about keeping people off the lawn. And maybe he didn’t mean to come off so aggressive, maybe he hasn’t been taught that whistling at women, at anyone, is creepy. Maybe. Or maybe that’s too generous.

Anyway, the whistle sent a message. Without words, it said, You don’t belong here. And his whole attitude taps into something deeper about control, ownership, and the long-standing battles over who gets to claim and enforce the boundaries of nature.

The history and drama of lawns goes way back. Even before colonial times, the lawn was a marker of status, a symbol imported from proper English estates where hemmed, cash-green yards were markers of status and power. In America, the lawn is wrapped up in the American Dream, an essential part of the white-picket fence promise of purity, elitism and capitalism. I’m trying to avoid making a pun about how the quest for the perfect lawn gained traction or led people to thirst for more, but that’s what happened. A whole industry has been built on convincing people they need to tame the ground that they walk on. By 2030, economic experts predict lawn care will be a $68.66 billion industry in the United States (compared to $17.46 billion in Europe). That’s billions invested in toxic herbicides and pesticides that destroy ecosystems and pollute waterways. And even more billions of gallons of water poured out to maintain that emerald-green hue and the artificial sheen of power and control.

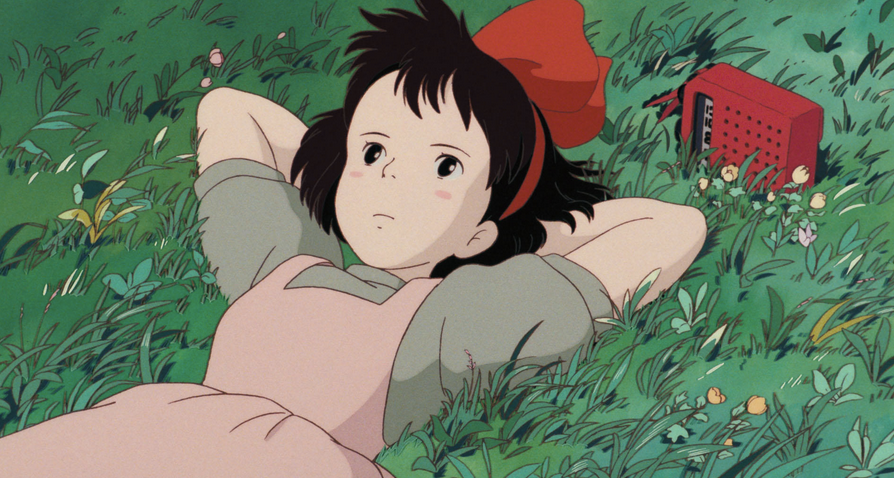

Obviously, people are mad, especially those who live in drought-stricken areas. They’ve started movements like “Kill Your Lawn,” where home owners replace their lawns with native plants that require less water or “No Mow May,” which encourages letting the yard grow wild to support bees and other pollinators. Because when a yard stops being a manicured, uniform lawn, something magical happens — grass grows and a whole society develops within it. The grass becomes a habitat for insects, small animals, and microorganisms that enrich the soil, increasing biodiversity. Scientists have learned that blades of grass actually “talk” to each other through their root systems. That they have their own language to share resources, warn each other about threats and channel information. I imagine it’s like a whole Richard Scarry grass world with highways and conversation networks, relationships and communities that are built around blades of grass growing as part of something bigger than themselves.

And when grass can just be, it knows how to thrive. But blades of grass, which Walt Whitman celebrated as, “no less than the journey-work of the stars” have become so politicized, twisted into symbols of elitism and uniformity. Grass is like that person who used to be cool or could be so cool if they stopped talking about their job all the time. I’m not saying it’s grass’s fault, but it’s become kind of a mascot of obedience. Each blade of grass is expected to stay in its place and conform to the roundup-ready protocol. If any of them dare to grow wild or too tall – then it’s off with their heads.

Drawing these rigid borders isn’t just about taming nature but also exerting dominance over other people. Like, if I can own nature, I can control the ground, and then by extension, I can control the people who set foot on my grass. I can even whistle at them. And while there’s nothing surprising about some dude trying to dominate Mother Nature and telling me where I’m allowed to put my body and how I should move through the world, there is a question of how I should respond to it.

And I’ll confess something – the worst part of the interaction with the guy wasn’t actually the whistle. The worst part was that I turned around, and in doing so, I responded to being whistled. And even though I quickly rolled my eyes and kept on walking across the grass, I still had that obedient reflex. Even as I tried to tune out his red-faced shouting, there was still a little voice inside my head holding a clipboard and scolding me, or at least making me second-guess if I’d done something wrong.

That internalized voice is what Jenny Lewis refers to when she sings about the “the little cop inside that prevents me.” A tiny authority figure that polices the way we talk and dress, the way we move through the world. That voice is a legacy of internalized oppression and a culture that tells us we’re not supposed to take up too much space.

But taking up space is the healthy response. Last week I wrote about Audre Lorde’s writings on self-preservation, and how that word means more than just surviving. Self-preservation is about grounding ourselves through art, rest, and nature. These acts of reclaiming space, time, and humanity have sustained me during a transition when there’s no certainty. I’m unemployed, my circle of friends has shrunk, my country is a mess, and even my apartment, once a sanctuary, is now just a temporary home.

The only permanence is change. And to quote Remy from Ratatouille, change is nature. That’s why I’ve found it so comforting to be in the thick woods, under the yellow trees, jumping into running rivers and feeling the grass beneath my feet. When I come back from an excursion, I notice how even the green spaces in urban and suburban areas feel artificial. A sign (or a whistle) instructs me to “keep off!” I was recently in Vienna where there are parks that don’t even allow dogs to enter on a leash. I get that cities are trying to maintain a certain aesthetic, but at what cost? The idea that we’re not allowed to be a part of nature, that we’re not allowed to touch grass, divides us from our environments and ourselves. Because we are nature, and the more we’re driven away from it, the more division will exist inside our own bodies. This separation puts our humanity at risk as well as our ability to connect with each other. As Audre Lorde wrote, “the future of our earth may depend upon the ability of all women to identify and develop new definitions of power and new patterns of relating across difference.” These patterns – of connection, of belonging – are about our relationship to each other and also our relationship to the ground itself.

I was reminded of this last summer when I visited the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. I bypassed the crowd there to see the Andy Warhol exhibit and ended up in a basement corner looking at an enormous wheatfield. A wheatfield inside a museum, or at least a documentary about one. Agnes Denes’s Wheatfield – A Confrontation (1982) was an art installation that transformed a two-acre landfill in lower Manhattan next to the World Trade Center. The wheatfield was a critique on urban development and a symbol of nourishment in a city where extreme wealth tramples over extreme poverty. But planting a wheatfield in New York City was also a gesture of hope, that people could restore their connection to nature. In the field, there were paths that allowed visitors to experience the quiet of golden colors and swishing, towering stalks.

Wheatfield, however, was only a temporary project. That fall, the crop was harvested and the land was reclaimed by developers. Today it’s Battery Park condos and pavement, but the golden field’s brief existence in the shadow of skyscrapers raised questions about what capitalism steals from city dwellers and what life might be like if there was more access to green space, which is rapidly disappearing everywhere.

There’s something so heartbreaking about the end of that project. It feels like a metaphor for all the wheatfields inside our own bodies and souls, all the stretches of nature inside us that get sacrificed for grind culture or societal pressure. We give up pieces of ourselves for our jobs and relationships, to fit into a social group or meet the expectations of our culture. We sit at desks, stare at screens and get lonely, forgetting that we’re nature just as much as the blades of grass and the stars and the open sky. That we deserve to be free and not follow orders from little cops.

The more time I spend connecting to nature, the smaller my little cop gets. That might mean I’ll continue to fall even further behind society’s expectations of me: I’m not married. I don’t have children. I don’t have a job or own a home with a big lawn. In the eyes of many people, something has gone wrong in how I live my life. But being untethered is also freeing – there’s less pressure to follow the rules. I walk on the grass, I leave the party when I’m not having fun, I cry in public because this the space I want to take up in my life and the boundaries I want to draw. Just the other day I was walking in the woods and crying because life is hard, and sometimes there’s no clear thing to do next. I let it out until my eyes were swollen, a mess of tears and snot. I was with my dog and trying to keep up a game of fetch between tears. Then at one point I heard someone call out. “Excuse me!” It was a woman’s voice. “Is this yours?” I turned and she was holding the muddy ball that had gotten lost along the way. As I got closer, she saw my puffy face and red eyes, but she didn’t look at me with fear or pity. She smiled, handed the ball back to me, and I said thank you and continued walking.